August 2022

ART AND POETRY

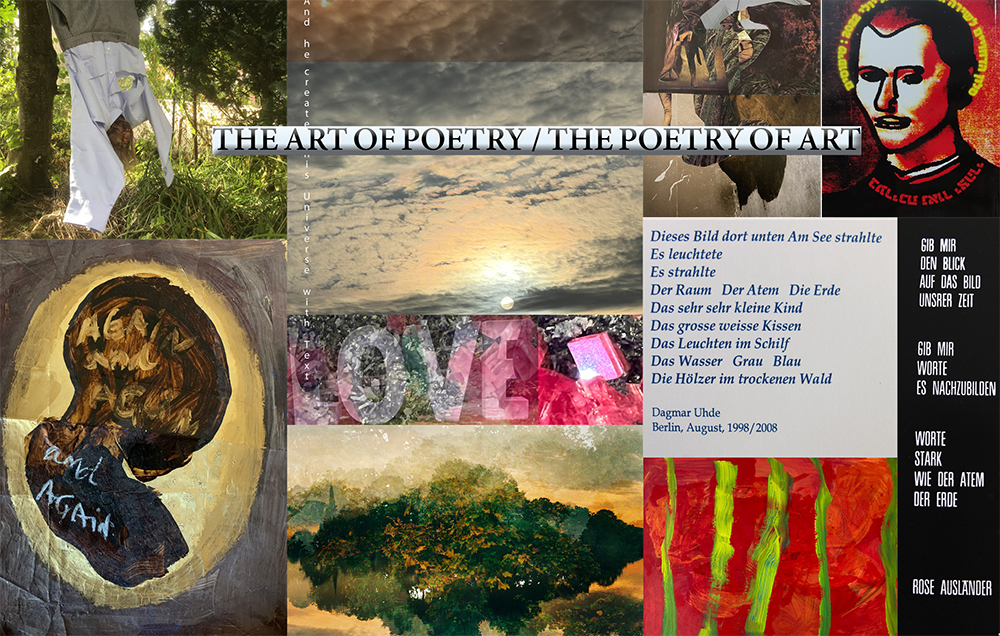

art of Poetry / Poetry of art” is due to open on September 8th at Drimmer/ The Fourth Wall art space. The exhibition is curated by Doron Polak.

The visual artists who participated in this show were inspired by poetry, or felt that their work responded to poetry. In his ‘Poetics,’ Aristotle contends that both painting and poetry are forms of ‘mimesis’ – a term traditionally translated as ‘imitation,’ but today more often as ‘representation.’ The 19th century painter of historical scenes, Tito Lessi, said that painting and poetry are similar in that they both “make absent things present.”

The mimetic properties of art are demonstrated in the story of Kora of Sicyon, as recorded by Pliny the Elder. When her lover left Corinth, Kora drew the outline of his shadow on a wall. Her father then modelled the lover’s face in clay from that outline, thus ‘inventing’ the representation of a figure in clay. Pliny also relates the story of Zeuxis, a painter in Ancient Greece, renowned for creating illusion through light and shadow. So real was his painting of grapes that birds flew down to peck at them. But when he then tried to pull aside the curtain behind which his rival Parrhasius’ painting was concealed, Zeuxis discovered the curtain itself to be a painted illusion.

We still think of art as the ultimate illusion. Aristotle asserts that it is in the nature of a human being to seek knowledge. Philosophy and poetry are a product of the human desire to know. This is made possible by what he calls tekhne – ‘craft,’ ‘skill’ or ‘art’ – the pursuit of knowing through making. Aristotle believed that the evolution of human culture is largely the evolution of tekhne. So too the production of poetry can be seen as tekhne: through its creation, the intrinsic knowledge contained within its form becomes intelligible.

For Martin Heidegger, a work of art is never merely depiction, but revelation – Parrhasius’ painted curtain forever being pulled back. In “Der Ursprungs des Kunstwerkes“ (“The Origin of the Work of Art,” 1950), Heidegger argues that the creation of the work means the building of a world. Art’s form is in conflict with the world that emerges from its making; the intrinsic truth is in a struggle with its extrinsic medium – paint, for example, or words. The outcome is what he terms aletheia – an “unveiling,” a revelation that gives us at least some of that knowledge we seek as humans.

Through mimesis, visual art and poetry both have this power. Indeed art can also inspire poetry and poetry art. Examples are Rainer Maria Rilke’s 1908 poem, “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” which is a reflection on existence, John Keats “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” William Blake‘s ‘Illuminated Books,’ and the Surrealists‘ blurring of the line between written word and painted image. In contemporary art, a prime example is the conceptual work of Jenny Holzer – the billboards and electronic displays that make up what is called “word art.”

But perhaps the ultimate apotheosis of the intertwining of poetry and visual arts is found in the example of Titian and Philostratus. In the Worship of Venus (1518), the Renaissance Venetian painter Titian depicts a crowd of plump cupids gathering apples, wrestling, climbing trees, even playfully aiming arrows at each other. This scene in turn is a visualization of words written by 2nd century AD Greek author Philostratus in his book Imagines. But these words themselves are a description of a visual painting that was apparently displayed on the wall of an aristocratic villa in antiquity, long lost to the world [footnote 1].

Image inspires text; that text then inspires image. The circle can loop infinitely, as long as there is still more to reveal.

Henie Westbrook

August 2022